Back in November, we

started working our way through

The Integral Urban House, a seminal book on urban homesteading, with the objective of updating the book's excellent but 35-year-old data. We took a few month-break but we're back and ready for some Chapter 2 action.

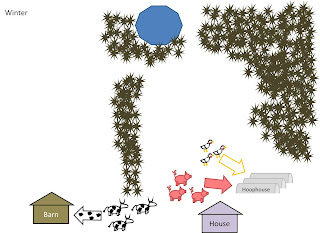

Chapter 2 is an introduction to the material and energy balances of the IUH, and also the trippy graphics that characterize the book. The authors give a high-level overview of the energy flow through their homestead in terms of btu/week, the IUH's nitrogen cycle in terms of lb/week, and a number of other nutrients.

|

| On their 0.2-acre lot (in Berkeley, CA), the Integral Urban House was able to produce 43% of their food and 44% of their energy needs (for five adult humans) while drastically reducing their outputs to the sewer and landfill. 1Wikipedia, 2EPA |

These graphics are remarkable for two main reasons--the visualization of energy and nutrients as resources to be recycled (and ways to recycle them) instead of inputs and outputs that flow linearly through the homestead system, and the degree of quantification achieved by the authors (thorough even by today's standards!). Along with cyclically-flowing resources, the authors also discuss the benefits of a certain degree of redundancy for generating these resources and capitalizing on the byproducts of their use. For example, heating by passive solar energy when it's sunny, but having a wood stove for cloudy days, and having the option to send organic wastes to worms, chickens, or compost (if both the worms and chickens are full). The same concepts were being simultaneously pioneered by

Bill Mollison,

David Holmgren, and

Sepp Holzer, and introduced decades earlier by Joseph Russell Smith (

Tree Crops book linked

here),

Toyohiko Kagawa, and

Masanobu Fukuoka (among others).

Perhaps an update to this chapter would be a carbon balance and cycle. Not just in terms of CO

2 consumption and emission, but soil and plant carbon balances. Many homesteaders, both urban and rural, are continually on the search for high-carbon substances for balancing compost composition, increasing soil organic matter, firewood, building materials, etc.

It seems that a significant fraction of 'sustainable living' can be attributed to high-fertility soil, which can often be attributed to organic matter imports from outside the homestead property. These materials are wonderful amenities

now because they are readily available, cheap (or free), and often considered waste by non-homesteading-minded folks. But for true sustainability, shouldn't the organic materials come from the homestead property itself? Surely if everyone tried to 'live sustainably,' the hundreds of pounds of free horse manure and old cedar fence panels from Craigslist (way more exciting than it sounds) would quickly vanish, accompanied by an eventual decrease in the soil fertility/sustainability of a given homestead.

The natural follow-up question is, what is the minimum acreage required to make a 'carbon-neutral' homestead possible? The answer to that question will obviously vary widely by region--five acres in northern Georgia will produce way more carbon than five acres in the Nevada desert. But if, like in the Integral Urban House, we convert everything to units of energy and compare with other studies, we can come to a ballpark (or at least average) number.

Figure 2-4 of the IUH says they import 150 thousand british thermal units (kbtu) as non-vegetable food, 1,250 kbtu as fuel (petroleum, natural gas, electricity, and wood), and use about 5,000 kbtu as solar energy to grow plants. Then they import another 196 kbtu as vegetable-type groceries, 120 kbtu as animal feed, and 19 kbtu as meat groceries, bringing the grand total to 6,615 kbtu per week, or 343,980 kbtu per year.

The famous

Billion-Ton Study, published by the US Department of Energy in 2005, said that of the 2.263 billion acres encompassed by the US, around 50%, or 1.132 billion acres, is suitable for biomass production (pg. 20). This amount of land could produce 1.366 billion tons (3005.2 billion pounds) of biomass (feedstock for fuel for them, but approximating food, fuel, etc. for us) per year (pg. 17), with some modest assumptions about yields and recovery costs. Since the combustion energy of biomass is

conservatively around 6.45 kbtu/lb, that means that it should be possible to produce 8,565.4 kbtu per acre per year. Dividing the number for the IUH by the number from the DOE gives 40.2 acres for the IUH to be perfectly balanced. There were five people living there, so that works out to about 8 acres per person. (Using the upper range of 8.20 kbtu/lb for biomass combustion drops that number to about 6.3 acres per person).

|

| Crude calculation for minimum number of acres required per person for homestead carbon neutrality, based on an IUH-level lifestyle and diet. |

That number represents an average across the US and is a little higher than the number derived by a

Swedish university organic farm last spring of a little over one acre per person. However, the Swedish study used a base case of 80 acres, which isn't infinitely down-scalable: it wouldn't work to grow 1/6 of a cow on 1 acre, for example. The Swedish study also put a high emphasis on food calories regardless of source, which strongly emphasized dairy and de-emphasized vegetables and meat. Therefore, although our calculation here is a little more crude, 8 acres per person is probably more realistic, and maybe even a little low if one wants to produce his own grains, dairy, and building materials self-sufficiently. Also, don't forget to take advantage of direct solar and wind energy, which have efficiency ceilings considerably higher than photosynthesis (which produces biomass).

Chapter 2 of the Integral Urban House ends with a hopeful wish that, much like hot rodders in the 1970s or silly television in the 2010s features folks competing to have the most aristocratic vehicles and houses (or rides and cribs, if you prefer...but

tyrannosaurus rex eggs?), future mainstream endeavors will feature a sort of contest to see which crib can be most integrated and sustainable. The authors might be disappointed with how far the mainstream has come in the last 35 years, but maybe there's a

glimmer of hope?

Plus, there's always the internet, with it's endless fountains of sustainability inspiration!

Have you measured the balance of energy and resources on your homestead? How sustainable did you come out? What's the size of your homestead and how much organic matter do you import? Let us know in the comments section below!