On Tuesday, we established that the process of leaching ash water likely extracts both potassium carbonate and potassium hydroxide. But we also want to know the relative proportions of each because if we're going to use the ash water for leavening, we have to increase the amount of acid in the recipe to neutralize any potassium hydroxide, if it's present. Today, we're going to titrate some ash water.

We can approach this task in two ways. We could 1. trudge through it with the bored disdain of an analytical chemistry student ("is it ever going to change color?"), or 2. pull out a bottle of last spring's dandelion wine, blast some banjo music, and turn this nerd party into the best date night ever! If you've been following this blog for any length of time, you know we're about to down some libations and do some titrations!

Essentially, what we're doing in the titration is to take the ash water, which is very alkaline (high pH) and add a solution

of acid a little bit at a time until we get to the point where all of

the hydroxide and carbonate are converted to water (from the hydroxide)

or water and CO

2 (from the carbonate), at which point the water will be

very acidic (low pH). If we keep track of the amount of acid we added, we can

figure out how much carbonate we have, and then back-calculate to figure

out how much hydroxide. It's like magic, but better--it's math!

The chemistry that's happening is this: first, all the acid we add (e.g., hydrochloric acid, HCl) is eaten up by the hydroxides:

KOH + HCl = H

2O + KCl

(That's

why, if both are present in the ash water, we need to add more acid to

our biscuit recipe to get the leavening effect we want.) Next, all the

acid we add reacts with the carbonate to produce the bicarbonate:

K

2CO

3 + HCl = KHCO

3 + KCl

Finally,

all the bicarbonate reacts with the acid to produce carbonic acid, some

of which will convert to dissolved CO

2, and some of that will convert

to gaseous CO

2 and bubble out of solution (that's the leavening effect we're trying to get when we combine acid and baking soda in our biscuits!):

KHCO

3 + HCl = H

2CO

3 + KCl

H

2CO

3 = H

2O + CO

2,(aq)

CO

2,(aq) = CO

2,(g)

For what it's worth, the acid that reacts with KOH in the first reaction above could also be H

2CO

3, which would generate K

2CO

3 and, if there were enough H

2CO

3 to go keep it going, KHCO

3. So, bubbling CO

2 through the ash water, which generates H

2CO

3 by

Le Châtelier's principle (i.e., it pushes the above reactions backwards), would help boost the leavening power of the ash water. In the absence of bubbling CO

2 , it can help a little to leave the ash or ash water sitting out exposed to the air before using it, because it will absorb CO

2 from the atmosphere, to some extent.

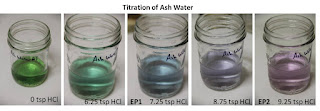

What are we looking for in the titration?

This book

has a great visualization of what you'd expect to see when titrating carbonates, hydroxides,

or a mix of both. The only trick is that we don't have a pH meter to

measure the titration progress directly, so we need a pH indicator

(i.e. a molecule that changes color in response to changes in pH) instead.

This site

explains that phenolphthalein and methyl orange make good indicators for

this titration, while the book linked above says bromocresol green is

also good for the second indicator.

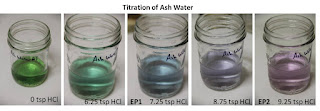

What makes an

indicator good for a particular titration is if it changes color at the

same pH as one of the endpoints we're trying to titrate (carbonates for

us). The chart below shows where the indicators mentioned above change

color in relation to the species of carbonate in the ash water. Our kitchen doesn't have any of the three indicators commonly used in the lab, but we do have some red cabbage juice, which is a cool enough indicator to do

both endpoints. Hooray for cabbage!

|

| Phenolphthalein

changes from pink to colorless just as all of the CO32- is used up

(endpoint 1, or EP1, at pH 8.4). Similarly, bromocresol green changes from blue to

yellow and methyl orange changes from yellow to red just as all the

HCO3- is used up (EP2, pH 3-4). (Source.)

Happily for us, cabbage juice changes from green to blue near EP1 and

from colorless to pink near EP2. Cabbage juice solutions don't really

go completely clear, but they become a very pale purple, and then the first

tinges of pink should indicate our endpoint. |

Titrations with indicators in general are

a little tricky because the color change is always

somewhat subjective. But we can practice on a few solutions of sodium

hydroxide and sodium carbonate first, to get a feel for what we're

looking for.

But before we can do that, we need a strong acid to titrate our solutions with. We

picked up some muriatic acid (HCl) from Lowe's and diluted it from

31.45 wt% (10 M) to 0.05 M (essentially, 1 teaspoon (5 mL) into 500 mL

(a little over 2 cups) of water to make 0.1 M HCl, and 1 cup of that

plus 1 cup water to make 0.05 M. NOTE: if you're following along at home, put on safety goggles and gloves before you start playing with 10 M HCl. Also, HCl doesn't get along very well with

almost any metal, including stainless steel. So, if you're diluting in

the kitchen, don't use your nice metal bowls and measuring spoons.

Plastic and glass only for this exercise!

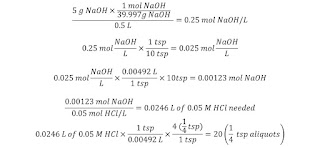

Now, we

need some standard solutions. First up: just NaOH (5 g in 500 mL water

to make a stock solution), diluted 1:10 (1 teaspoon of the stock

solution plus 3 Tablespoons water), and added 1 teaspoon of the indicator solution. Here's the math to show how much acid we

expect to need to add. The smallest plastic measuring device we have is 0.25 teaspoon, so that's what we're going to count our titrations by.

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 20

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 0

Large canning jar of 0.05 M HCl, 1/4 teaspoon measuring device, small canning jar of 1 g/L NaOH in place...ok, ready, go! 1 quarter-teaspoon, swirl, 2 quarter-teaspoons, swirl, 3 quarter-teaspoons, swirl...

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 13

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 0

EP 1 + 2 error: -35%

|

| 0.05 M HCl added in 0.25 tsp aliquots. That's the smallest non-metal measuring spoon we have! |

Hmm...so,

not terribly accurate, (see note at the end of this post) but we would predict all hydroxides and no carbonates, as

expected. The indicator pretty much skipped the blue and purple phases

and when straight to pink-ish.

Second standard

solution: just Na

2CO

3 (5 g in 500 mL to make a stock solution, diluted

the same way). We can to do the same math (substituting the molecular weight of Na

2CO

3 for that of NaOH to get to:

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 7.55

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 7.55

And...the results:

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 5

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 5

EP1 error: -34%

EP2 error: -34%

|

| 0.05 M HCl added in 0.25 tsp aliquots. |

So,

similar errors, but again, we would conclude based on the volumes to

endpoint 1 and endpoint 2 that we have just carbonate in solution, which

is true.

How about a third standard solution, with a mix of the two? 5 g NaOH + 5 g Na

2CO

3, similar math to get to:

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 27.55

Calculated number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 7.55

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 23

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 6

EP1 error: -17%

EP2 error: -20%

|

| 0.05 M HCl added in 0.25 tsp aliquots. We went one past our supposed endpoint to see how pink it would turn. |

Better, but still large enough errors to make an analytical chemist cringe. However, feast your eyes on this set of numbers:

Calculated ratio of carbonate to hydroxide: 0.377

Experimental ratio of carbonate to hydroxide: 0.353

Error: -6.5%

Booya!

Less than 10% error is not bad for kitchen chemistry. It looks like we might be able to use this

technique with enough accuracy to figure out relative amounts of

hydroxides and carbonates in our ash water.

Now for

the real stuff. We made the ash water by mixing 0.5 cups wood ash (mainly elm) plus 0.75 cups boiling water, mixed

well, and left to settle for several days (mainly because of convenience; it was well settled by the next morning). We tried one titration undiluted, but the ash water turned out to be really strong stuff, so we ended up diluting the ash water 1:10 and titrated that with

0.05 M HCl. Here's the stats:

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get to EP1: 29

Actual number of 1/4 teaspoon aliquots to add to get from EP1 to EP2: 8

Experimental ratio of carbonate to hydroxide: 0.381

(Experimental ratio of hydroxide to carbonate = 1/0.381 = 2.625)

|

| 0.05 M HCl added in 0.25 tsp aliquots. |

Whoa!

So, for every 1 molecule of carbonate in our ash water, there are 2.625

molecules of hydroxide. Or, stated another way, the leavening

power-influencing parts of the ash water are 72.5% hydroxide and 27.5%

carbonate.

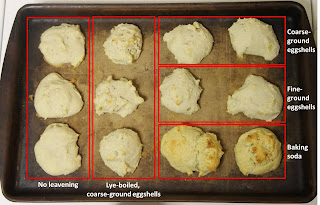

What does that mean for baking with ash

water? If we had only carbonates, we would have to add enough acid to convert the carbonate to the

bicarbonate, and then convert the bicarbonate to CO

2. But since we

know that our acid will first react with the hydroxide, we need to

increase the acid on top of that. If a recipe is starting with baking

soda (sodium bicarbonate) and an acid, we would want to double the

amount of the acid to get the same effect from the carbonate, and then

roughly

triple that amount to neutralize the hydroxides. Or,

overall, if we're replacing baking soda in a recipe with ash water, we

should have to add

six times as much acid as the recipe calls for to get the same leavening effect.

Also,

it's probably good to know how much bang for the buck we can expect to

get from the ash water. Although we noted that our quantification isn't great, we were consistently predicting 20-35%

less of each component than was actually present. So, for the

carbonates, our titration calculates that there is 0.000492 mol K

2CO

3 and

0.00129 mol KOH per teaspoon of ash water, which works out to 0.067 g K

2CO

3 and 0.072 g KOH. If we multiply those by 1.25 to account for the

20-30% error in our titration, it works out to 0.085 g K

2CO

3 and 0.091 g

KOH. Since the baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) has a

bulk density of 801 kg/m3

(0.801 g/mL), and 1 teaspoon = 4.92 mL, each teaspoon of baking soda contains about 3.94 g of NaHCO

3. Therefore, one teaspoon of our ash

water has about the same potential leavening power as 0.022 (1/46)

teaspoon of baking soda. (Actually, it has slightly less leavening power because KHCO

3 weighs more than NaHCO

3.)

Of course, it will only reach that

potential if we add enough acid to neutralize the hydroxide and convert

the carbonate to bicarbonate. As we mentioned above, the best way to do that would be to bubble CO

2 through the ash water, which will convert both the CO

32- and the OH

- to HCO

3-. Ideally, we'd do that until the ash water (with a bit of indicator) turned blue. That would increase the leavening power up to about 0.04 (1/22) teaspoon of baking soda. The other readily-available way to increase the leavening power would be to boil off most of the water to concentrate the carbonates.

With this knowledge in hand, we can move on to the delicious finale. Stay tuned for more biscuit trials!

...

Ok, as a follow up, we were slightly disturbed by the absolute errors in our titrations, so we did something that we should have done beforehand--mix up reference solutions to compare colors. To get the first endpoint is easy--just mix baking soda into water and add the indicator. All of the relevant species are present as the bicarbonate ion, so the pH is right at the first endpoint. For the second endpoint, we added 0.25 teaspoons of our NaOH stock solution (5 g NaOH in 500 mL water) to 100 mL of vinegar, which should give a mixture with a pH of about 3.08 (calculations available on request!).

|

| That second endpoint (on the left) is a lot pinker (i.e., lower pH) than what we were calling our endpoint! No wonder our errors were so large--we should have added a few more aliquots of 0.05 M HCl to each solution before calling it done. Of course, that wouldn't help the first endpoint much; most of the solutions went from green-blue right to purple. Guess we better stick mostly to calculating ratios with this method. Also, if you ever need a nerdy gender-reveal idea for your future baby, here you go! |