We recently finished reading Joel Salatin's You Can Farm: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Start and $ucceed in a Farming Enterprise. It's a good read, although at 450 pages, not a quick one. The book is an overview of the all factors Salatin estimates to be the particularly important in starting a profitable farm. It brings this breadth at the expense of depth, but the 'how-to' is presumably in some of Salatin's other books, Pastured Poultry Profits and Salad Bar Beef (which we haven't read yet). You Can Farm is full of anecdotal advice from Salatin's experiences with pastured livestock (especially chickens, beef cows, and pigs, with turkeys and rabbits also frequently mentioned), which is valuable, but in our opinion doesn't justify owning the book. Check it out from the library, take a few notes, and return it. At times, Salatin incorporates enough of his own philosophy to make wary readers consider a second opinion--which is fortunate, if inadvertent--but the main theme (of the farming part) is happily focused on permaculture principles. The book is especially valuable in that it weaves together farming practices and business practices to explain why incorporating these principles is the most surefire way to make a farm profitable. It's important to keep in mind, however, that this is a book about profiting from a

farming enterprise, independent of what one may prefer to grow for his

own consumption.

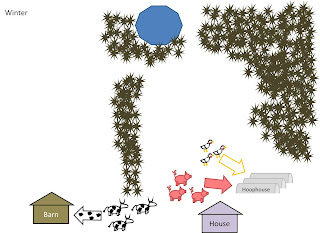

Salatin focuses on raising livestock, but makes sure to point out many other enterprises that he's seen work just as well (even though he doesn't have as much personal experience in them). He seems to have settled on the conclusion that the best return for time invested lies in pasture-raised meat and eggs. He makes use of a few primary functions for each type of livestock that complement the others, which allows him to 'stack' enterprises, or produce multiple products from a piece of land in any given year:

•Cows harvest grass and fertilize pastures

•Chickens follow cows or pair with rabbits to control pests

•Pigs aerate compost and till soil, fertilize soil, and sometimes repair earthen dams

One of Salatin's most salient pieces of advice is to prioritize the acquisition of farming experience over the acquisition of a farm (if the goal is to have the farm as a primary source of income). His opinion (which he bases on his own observations) is that doing things the other way around leads to failure, despair, and in many cases, bankruptcy. The key, as Salatin mentions, is to not require significant income from the farm for 5-10 years. Thus, it's much safer and less stressful to start small and part-time, and scale up from there once the farming and marketing model have proven themselves sufficient. In short, don't go into debt to switch vocations to farming. (As an aside, we note that similar advice could be applied to acquisition of a homestead since some form of cash flow will always be required for things like property taxes, even if no external inputs are needed to survive.)

In sum, You Can Farm is mostly full of good advice, moderately entertaining, and worth checking out from the library, but we don't intend to make room on our bookshelf for our own copy. Have you read You Can Farm? What did you think about it? Are you 'stacking enterprises' as Salatin recommends on your farm or homestead? Tell us about it in the comments section below!

No comments:

Post a Comment